The Negative of 1

What’s so wrong about being by myself?

Some clients speak of being alone as an earned reward. The freedom of being on their own allows them power to direct their time without the encumbrance of compromise. I nod and agree. Being alone brings freedom and self-direction.

I also know that being alone can be a choice that is a not about freedom, but about enclosure and self-destruction. For those who embrace and support the splendor of being alone, but find themselves looking for answers in therapy, the rest of their story is not so nice.

The real part of their story is the reason for our meeting. It is the negative of 1.

There is nothing wrong with being alone. There is a freedom to self-direction without the compromise of others. But if the state of being alone is the majority of someone’s time it can be detriment and destruction, not freedom.

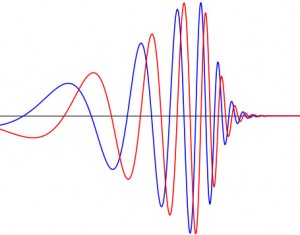

Often in life we point to the negative and try to repaint it in better light, to embrace it, to encourage others to accept our choice as willing and positive. But this is a cover, a form of fantasy lock. We are not designed to thrive as 1, alone. This state of aloneness, when it represents the majority of our time, is psychologically detrimental and physically destructive.

It is not easy to admit the absence of close friends and confidants in our lives. When asked to list best friends, allies trusted with secrets, or people in our lives who would come to aid us in crisis, clients who celebrate the power of alone attest they don’t need these relationships, they are better off alone. This is untrue.

It seems that through some mechanism we do not yet know, our mental and physical health are correlated to the fabric strength of our social interactions. Remove the social interactions and the health of an individual deteriorates in many circumstances.

Long-term studies of populations demonstrate that those with strong interactions and attachments within communities identify themselves as happier and healthier. Further, in a study of persons with cancer, those with strong support from social structures, family members, or communities of like-affliction, lived longer and healthier lives.

For clients in a consistent state of aloneness the corrective action is demonstrating that there are others like them, sharing the same displeasure of being alone, and not knowing what to do. The solution is to find attachment in a community of similar others, whether that be a club, organization, hobby, or activity group. For clients with addictions, this aloneness is correctable with participation in groups like Alcoholics Anonymous, where attachments are formed with others who previously found themselves alone and suffering.

Being alone is a choice, not an inevitable state. There is a community and social structure for every person. Find the one that is right for you. Make a choice not to be alone.